Close binary stars play several important roles in astronomy. For example, Type Ia supernovae, used to measure galactic distances, occur when a neutron star in a binary system reaches critical mass. These stars are also the source of x-ray binaries and microquasars, which help astronomers understand supermassive black holes and active galactic nuclei. But the evolutionary process of close binaries is still not entirely understood. That’s changing thanks in part to a new discovery of a close binary in its intermediate stage.

Stars shine thanks to nuclear fusion, which converts hydrogen into helium. Young stars are about three-quarters hydrogen and one-quarter helium by mass and over time the fraction of helium increases. The details of this process are complex, but as stars approach the end of their lives, a star is mostly helium with a layer of hydrogen surrounding it. What happens next depends on the star.

Because hydrogen is four times lighter than helium, older stars sometimes lose their outer hydrogen layer exposing their helium center. These are known as ᵴtriƥped stars. Some large stars, such as Wolf-Rayet stars, are hot enough that they cast off their hydrogen layer on their own. They make up ᵴtriƥped stars on the high mass side.

Smaller stars don’t create enough heat to fully cast off their hydrogen layer, but in close binary systems, a companion can ᵴtriƥ the hydrogen layer from its partner, leaving a small ᵴtriƥped star known as a subdwarf. Astronomers have observed several high-mass ᵴtriƥped stars with masses of more than 10 Suns, and lots of low-mass examples with a mass of the Sun or less. What they haven’t seen (until this latest discovery) is an intermediate-mass ᵴtriƥped star.

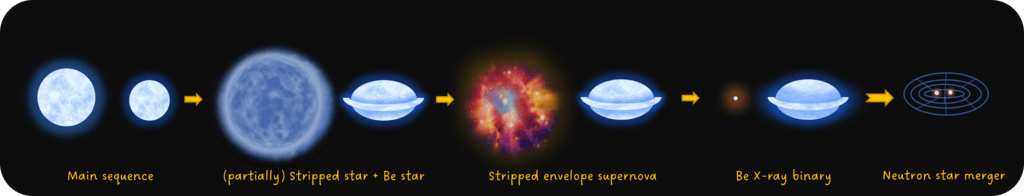

The evolution of close binary systems. Credit: Varsha Ramachandran, ZAH/ARI

The team looked at a system in the Small Magellanic Cloud known as SMCSGS-FS 69. At first glance, it looks like a blue supergiant star, but a close examination of its spectra found it’s a binary system with a Be star of 17 solar masses and a ᵴtriƥped star of about 3 solar masses. Based on theoretical calculations the ᵴtriƥped star likely had an original mass of about 12 solar masses. SMCSGS-FS 69 is the first example of a ᵴtriƥped star in the intermediate mass range.

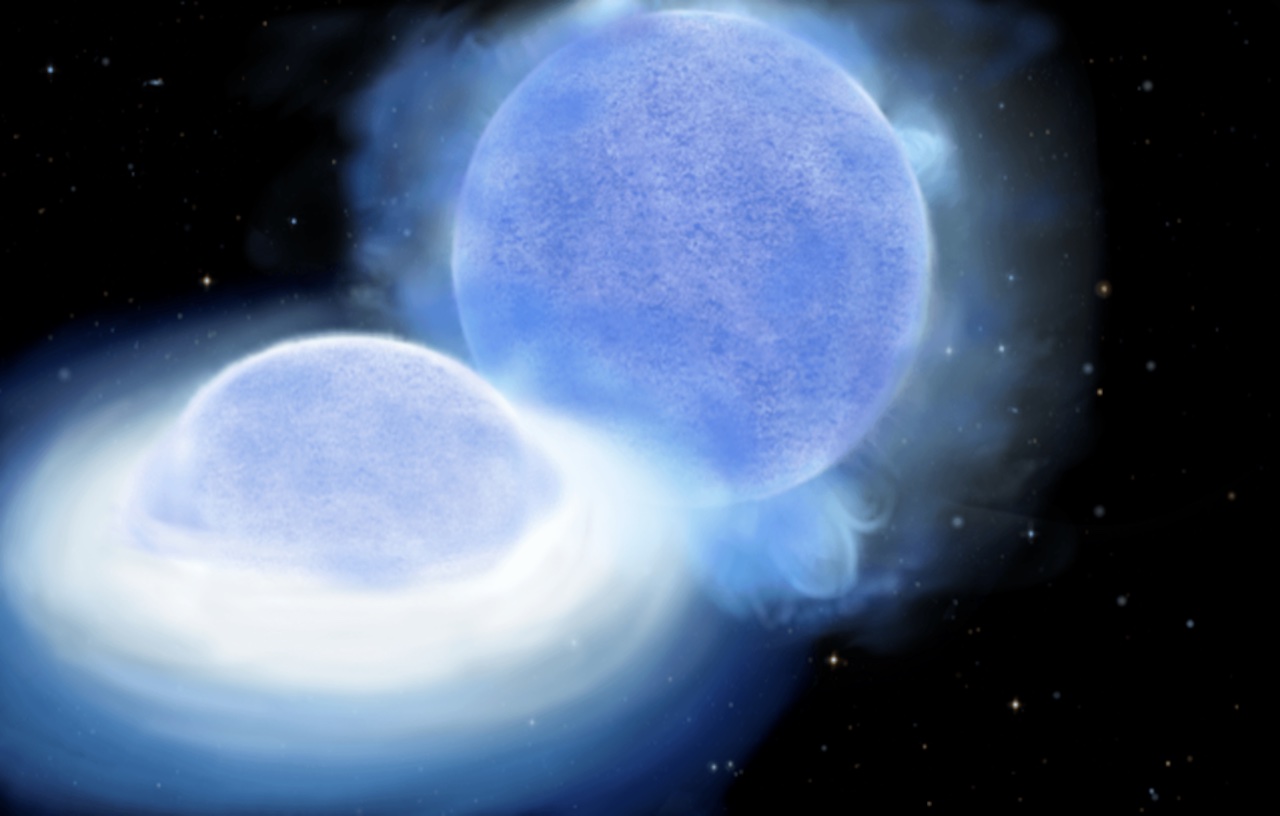

What makes this discovery important is that it shows a crucial stage in the evolution of merging stars. In the cosmically near future, the striped star will become a supernova before its core collapses into a neutron star. If the companion star survives this, the neutron star will eventually steal the hydrogen that was once stolen from it. The second star will be ᵴtriƥped, and will also become a neutron star or black hole. Finally, the two will merge in a cataclysmic explosion and become a single black hole.

Reference: Ramachandran, V., et al. “A partially ᵴtriƥped massive star in a Be binary at low metallicity: A missing link towards Be X-ray binaries and double neutron star mergers.” Astronomy & Astrophysics 674 (2023): L12.